No one knows precisely where St Andrew’s Priory was, but evidence suggests that it was close to where Newhouse Farm now stands (see the map on the Walk Through History page).

The mystery is surprising because the priory and the surrounding land covered 500 acres and would have included a number of buildings including a chapel, a dormitory, barns, a refectory and room to accommodate guests.

Various pieces of Pentewan Stone can be seen round the village which were probably once part of the priory , but they don’t give us any clues as to where they originated or from what building.

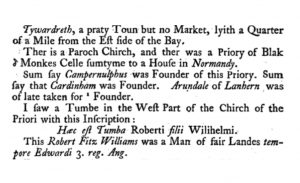

Poet John Leland, sometimes called the father of English local history, was in 1533 allowed to examine and use all the libraries in religious establishments. This is part of his local itinerary

As for the details, our thanks to medieval historian Nicholas Orme who writes: ‘The priory of St Andrew at Tywardreath was founded no later than 1149 by the family of Richard fitz Turold, a follower of William the Conqueror who acquired extensive lands in Cornwall, some of which he gave to the abbey of St Sergius and St Bacchus at Angers in France.

‘In due course, perhaps under Richard’s son or grandson, the abbey established a small satellite monastery at Tywardreath to administer its Cornish lands. It was staffed by six monks, all of them French and sent from Angers, one of whom acted as prior. The priory church and the domestic buildings lay to the south of the present parish church, which also belonged to the monks.

‘The priory got into difficulties during the Hundred Years War in the fourteenth century, when the English kings objected to money from their lands going to France. They took over the priory’s surplus revenues for long periods and made it difficult for monks to come from Angers.

‘By 1381 only the French prior was left, but after 1432 the prior was always an Englishman. Surprisingly, the priory survived nonetheless and acquired recognition as an English monastery. A revival under Prior Walter Barnecote (1451-96) led to Englishmen being recruited as monks which brought the total back to six.

‘This “Indian summer” came to an end under Prior Thomas Colyns (1506-35), whose rule was unsatisfactory, partly due to his alcohol problem. He was replaced by the government of Henry VIII in the spring of 1536, but the next prior lasted for only five months before the priory was dissolved by the crown, along with many other small monasteries in England. After this the church was demolished and the site is still to be excavated.

‘Two objects survive from the priory’s history. One is the tombstone of Prior Colyns in the parish church, and the other is a manuscript in the Cornwall Record Office which belonged to the priory: a book of Latin sermons along with the names of many Cornish men and women who gave money to the priory in return for prayers for their souls by the monks.’

The priory, which controlled Fowey, drew its revenue from a wide surrounding area that it is thought to have stretched as far west as St Anthony in Meneage, close to where Flushing now is. Some details of its revenue are given in the 1994 publication ‘Tywardreath Past and Present’ published by the Women’s Institute (out of print and now a collector’s item).

‘It’s possessions reached over much of Cornwall and into Devon’ the book explains. ‘By the beginning of the 13th century it owned all of the local churches, mills as far as St Breward, a number of manors, received the harbour dues from Fowey, tithes of tin, fish, wool and lamb from as far afield at Totnes, and even had the fishing rights on the Fal.

‘Naturally, too, they owned land round the village: over 300 acres with farms at Newhouse, Lower Lampetho and Colwith, and woods at Stoneybridge.

‘A priory in the Middle Ages was a considerable business, and its management depended on the sagacity of its priors.’

Over the years the income and importance of the priory declined so that by the sixteenth century its income was below £200 a year. As such it was classed as one of the smaller monasteries and was one earliest to be closed in the process known as the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Historian Nicholas Orme thinks it may have closed on August 10, 1536.

Its final years had been troubled largely because of the King’s determination to establish the Church of England. The prior, Thomas Colyns, came under immense pressure to quit. He’d defied Thomas Wolsey, the King’s chief minister, but like many others, could not resist Wolsey’s successor, Thomas Cromwell.

Tenacious Colyns certainly was, but according to some, he was also grasping and over-fond of drink. He appears to have stayed in the area until he died three years later; his tombstone can be seen in the church. He wasn’t the last prior, as many think, because Nicholas Guest, formerly of St Germans Priory (not a Benedictine monk, but an Augustinian canon) was brought in to manage things after Colyns stepped down.

When the priory closed there is no evidence of local anger or protest as had occurred elsewhere in the Pilgrimage of Grace. If locals could live without the monks, they might have felt differently about other religious changes that were to be imposed. Christianity underpinned everyday life, marked by statues, wall paintings, feasts, offerings, holy days, processions and Latin masses – all of which would be banned, restored and later banned again.

A trial trench dug as part of a community project in 2017

Nicholas Orme’s research tells us that the monks who left that day were: Robert Mortymer (sub-prior), Henry Bobyt, Madern Wylliam, William John, and John Stevyn. They were offered pensions and the choice of moving to another monastery, a short-term solution since they were all to close by 1539. They could also become parish clergy. William John may have become a chantry priest at St Cleer, but what happened to the others isn’t known.

Canon Nicholas Guest was promised a pension of £16 a year for life, or until he found a post as a parish priest. There is a record of him becoming the priest at St Winnow church in 1538. The fate of the priory servants is not recorded.

Following a dispute between the Arundell and Grenville families, the deserted priory was plundered. Within five years, Sir John Arundell had demolished some of the buildings and put the site up for sale. In 1542 it passed to Laurence Courtenay who kept the stone and timber of the church, cloister, dormitory, and chapter-house for himself. The lease expired that year and the Crown granted the site and nearby property to Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford, brother of Henry Vlll’s third wife Jane Seymour.

When the asset-strippers moved in things get murky. When a ship supposedly sank near Polridmouth it had some priory stone onboard which might have been preserved in the grounds of Menabilly. A map of England’s southern defences, made between 1539 and 1540, shows Tywardreath as a small cluster of houses, plus a church tower. There is no mention of a priory, but today there’s plenty of carved Pentewan stone to be seen around Tywardreath today which most likely originated from the priory.

Memories lasted rather longer than the priory itself. In 1584, a Lostwithiel barber remembered his time there as a scholar and his dinner-time task of watching over the tithe fish that the servants had laid out in the sun to dry. Five years later, two elderly men, Richard Gynnis and John Wattes, recalled Prior Colyns being ‘oftentimes overcome with drinck’ and that his butler was frequently sent to a merchant in Lostwithiel ‘to fetch divers bottels of wine’.

Nicholas Orme’s detailed history of the priory can be found in ‘Victoria County History’, Volume Two (London, 2010), Pages 284-96